The Philippine Education and Training System

Overview of Philippine Education

The Philippine education system covers both formal and non-formal education. Formal education is a progression of academic schooling from elementary (grade school) to secondary (high school) and tertiary levels (TVET and higher education).

The system is tri-focalized by law into basic, technical-vocational and higher education under three different agencies: the Department of Education (DepED) headed by a Cabinet Secretary for basic education; the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) headed by a Director General for technical-vocational education and training; and the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) under the Office of the Philippine President headed by the Chairperson of a collegial body of five Commissioners.

The Context

The nuances of the Philippine education system are best understood in the context of the following realities, among others:

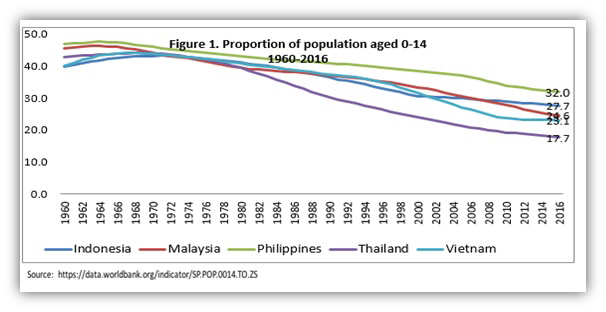

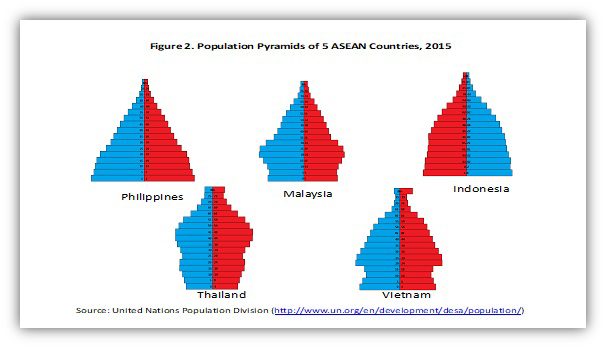

First, the formal education system is serving a school age population that has been consistently bigger than that of neighboring ASEAN countries in terms of percentage share of the total population—which for the Philippines now stands at about 104 million people. Figure 1 gives a rough picture of the proportion of the Philippine population that is expected to be in school. In addition, the age structure of the Philippines has remained pyramidal with a broad base, suggesting a sustained high demand for formal education at different levels (Figure 2) in the years to come.

- the dominance of private providers of qualifications vis-à-vis public providers in TVET and higher education;

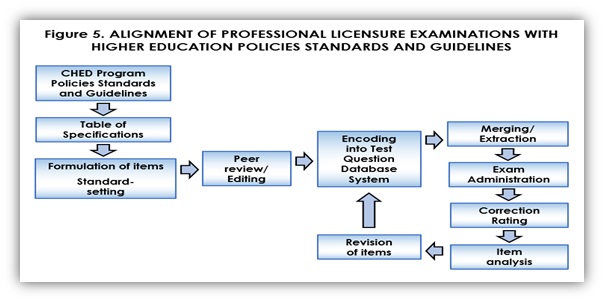

- a licensure examination system for regulated professions in addition to the education and training of professionals;

- the requirement of a first degree for specific professions, i.e. medicine and law;

- a separate General Education program in higher education to supplement a curriculum that may be too oriented to the specialized needs of industry and the professions; and

- a complex complementation of public and private quality assurance (QA) bodies that constitute the country’s system for quality assuring qualifications.

Reflections: Ongoing Reforms and PQF Implementation

The ongoing implementation of major education and training reforms render the description of the Philippine education and training system as “being in transition” apropos. It is reflective of the state of the Philippine Qualifications Framework in a period of transition which is targeted to end in 2022 when the major reforms and related changes would have been fully implemented and iteratively revised.

With respect to the K to 12 reform, it is important to note that the law was passed only in 2013 but attendant curricular changes in basic education, in anticipation of its promulgation, began in 2010—with inputs from TVET and higher education experts. The changes were completed before the roll out of Senior high school in 2016. Note that the first cohort of Senior high school who completed their basic under the revised curriculum graduated in 2018.

In higher education, curricular changes and revision of program standards commenced in 2013. These changes include the reduction of the General Education (GE) program from 63 to 36 units (1 unit=17 hours per term)—with some of the GE courses downloaded to Senior High School to give way to professional subjects and more intensive practicum or apprenticeship for the profession- and industry-oriented disciplines.

The shift to learning outcomes-based education—which occurred much earlier in the TVET sector--proceeded alongside the curricular revisions in basic and higher education. While the policies are already in place, their implementation at the level of teaching/learning and assessment on the ground is still uneven. As in the other ASEAN Member States (AMS), the requisite change in mindset and practice, especially in higher education, remains a major challenge. Nevertheless, significant headway has been achieved in opening the minds of teachers/professors in Philippine HEIs to the paradigm shift through the continuing advocacy of the country’s education and professional regulation agencies, reinforced by international Quality Assurance networks (e.g. the ASEAN Quality Assurance Network) and accreditation/assessment agencies(e.g. the ASEAN University Network) as well as the support of international agencies in conducting workshops or projects that enhance learning outcomes-based education (e.g. Support to Higher Education in the ASEAN Region [SHARE] and the Tuning Asia-South Asia Project to build a framework of comparable and compatible qualifications).

As to lifelong learning and the recognition of informal and non-formal learning, the Philippines continues to face the same challenge confronted by other AMS—i.e., that of bridging the gap between the policy articulation of LLL and the corresponding shift to learning outcomes on the one hand, and a deeper understanding and imbibing of the raison d’etre and LLL spirit, on the other. While implementation challenges are being met, it is notable that the policy shift to LLL has impelled the education and training agencies to expand existing programs that offer pathways and equivalencies to formal education.

Much work has gone, for instance, into the development of the Philippine Credit Transfer System (PCTS) to provide pathways between TVET and higher education. As of this writing, the TVET and higher education working groups have finalized the draft PCTS that will be going through the process of approval in the remaining months of 2018.

Being in transition to the full implementation of major education and reforms bear profound implications for PQF implementation. The state of the changes in the curriculum and program standards of higher education is a case in point. While these have been revised, some of the changes are still in the last stage of final approval by the Commission on Higher Education.

Basic Education

Structure

The current basic education system consists of a 13-year four-stage program with research-based curricula and methods of assessment that are appropriate to each Grade level at each stage. The stages are Kindergarten to Grade 3 (Primary School; 2) for pupils 5 to 8 years old; Grade 4 to 6 (Intermediate School) for pupils 9 to 11 years old; Grades 7 to 10 (Junior High School) for students 12 to 15 years old; 4) Grades 11 to 12 (Senior High School) for students 16-18 years old.

Formal basic education is provided mostly by public schools which constituted 83% of all basic education institutions in 2017.

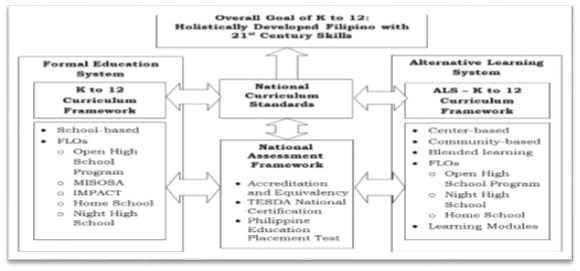

An Alternative Learning System is in place as a practical option to the existing formal instruction with DepEd authorized providers. Recognizing non-formal and informal sources of knowledge and skills, learners under ALS can take the Alternative Learning System Accreditation and Equivalency (ALS A&E) Test, formerly known as the Non-formal Education A&E Test which is designed to measure the competencies of those who have neither attended nor finished elementary or secondary education in the formal school system.

Current Reform

This basic education structure is a result of the K to 12 reform which requires Kindergarten and Senior High School. Pre-school education became compulsory in the Philippines only in 2012 with the legislation of the Kindergarten Education Act (Republic Act 10157) although many private elementary schools have prescribed—since the 1950s—one or two years of Kindergarten/Preparatory school for their learners who usually hailed from middle and upper-class families. These private schools include those based on Maria Montessori’s philosophy and the Waldorf School.

Prior to 2012, the Department of Education had pursued initiatives that eventually facilitated the institution of the Kindergarten Program. But two important breakthroughs led to the universalization of Kindergarten: the passing in 2000 of the Early Childhood Care and Development Act (Republic Act No. 8980) and the Barangay (village) Level Total Protection of Children Act” (Republic Act No. 6972). The former law sustained an inter-agency and multi-sectoral collaboration to guarantee delivery of holistic services to children aged 0-6 years old while the latter required all local government units to establish a day-care center in every village (UNESCO, 2016). These laws paved the way for the formally instituted integration of Kindergarten into the Department of Education’s Basic Education Program.

The Enhanced Basic Education or K to 12 Program is inclusive, promoting the right of every Filipino—regardless of age, sex, gender, ethnicity, cultures, and religion--to quality, equitable, culture based and complete basic education. Adhering to a lifelong learning framework, it provides opportunities for all learners to access quality basic education. For instance, learners in difficult circumstances who are prevented from physically attending classes are offered flexible learning options (FLO) to complete their studies while equitable and responsive educational interventions are crafted to give learners with special education needs the opportunities to actualize their potential.

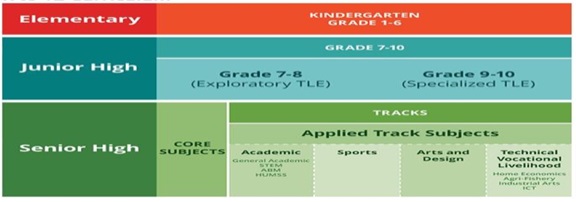

The Senior High School (SHS) Curriculum requires students to choose one of four tracks: 1) Academic, 2) Arts and Design, 3) Sports, and 4) Technical-Vocational-Livelihood. The academic track is further subdivided into four strands: 1) Accountancy, Business and Management (ABM); 2) Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM); 3) Humanities and Social Science (HUMSS); and 4) General Academic (GAS).

It is important to note that while Senior High School offers tracks and four strands within the Academic Track, SHS graduates--regardless of tracks—can gain admission to Baccalaureate degree programs. Tracking students early and making them progress within the same track is not acceptable in Philippine society, college education for the social mobility of their children being a universal aspiration of Filipino parents.

For this reason, all SHS learners, regardless of track, are required to take 15 core subjects (e.g. Statistics and Probability) to ensure that they are equipped with competencies required for specialization studies in their chosen SHS tracks. In addition, learners are expected to take 16 additional subjects in the Applied Track and in Specialized areas within their chosen Track. Geared toward the acquisition of common but critical competencies in SHS, i.e., English language proficiency, research, ICT, etc., Applied Track subjects are prescribed for learners in all tracks but are delivered with teaching- learning content and strategies customized to the requirements of each track. Figure 3 presents a picture of the basic education curriculum map.

Apart from the K to 12 reform, Philippine basic education has made the paradigm shift to lifelong learning and a learning outcomes-based approach at the level of policy and professional teacher standards and is currently refining its implementation in the classroom.

Figure 3. Enhanced Basic Education Curriculum

The Department of Education subscribes to School-based Management. While curricular freedom at the basic education level is limited for the public schools directly under its wings, the Department grants some level of autonomy to school heads in managing their schools—e.g. adopting innovative teaching methodologies, resource generation, teacher development programs.

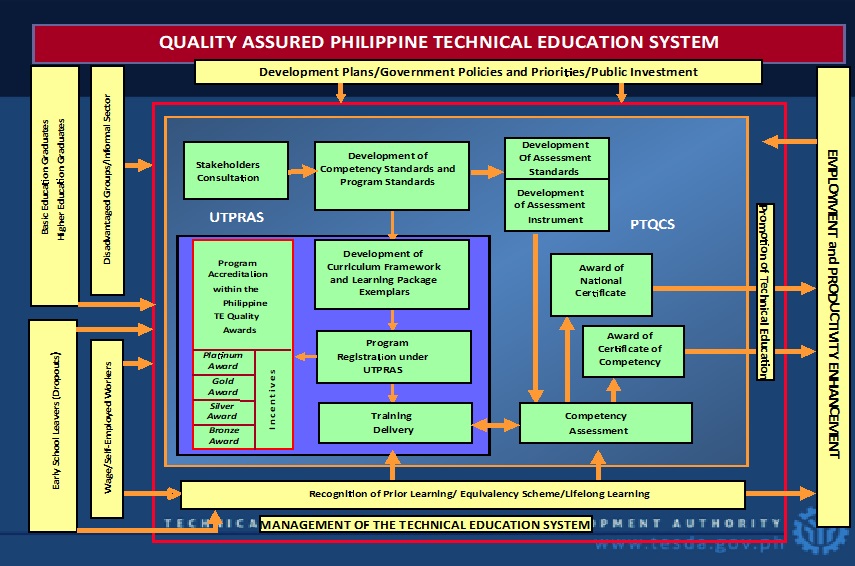

- A National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan anchored on national priorities as spelled out in the Philippine Development Plan and in the Investment Priorities Plan; current labor market information; and customer needs. National development priorities spelled out in the national plans as basis for the TESDA Board to draw up the national TVET policies and priorities;

- A system driven by competency standards and training regulations derived from industry requirements and specifications and guided by TVET priorities identified by the TESDA Board;

- Training Regulations as minimum national standards that serve as basis for the development of a competency-based curriculum and learning packages, competency assessment tools and standards and the training and qualification of trainers and assessors;

- Accessibility of the System to a broad range of customers including the unemployed, the underemployed, displaced workers, new entrants to the labor force, technical vocational institutions and enterprise-based training providers;

- Quality of training delivery premised on an efficient and Unified TVET Program Registration and Accreditation System (UTPRAS);

- The incorporation of a competency-based Philippine TVET Qualification and Certification System (PTQCS) that serves as the basis for the grant of national credentials including trainer and assessor certificates;

- Recognition of prior competencies acquired through alternative means and through related work experiences through a system of equivalency within the entire education system;

- Employment and productivity enhancement as ultimate metrics of the technical vocational education and training system to effectively bring about the effective matching of labor supply and demand;

- TESDA-enhanced TVET sector capability and capacity through financial resource management, human resource development, physical resource management, information management, marketing and advocacy, administrative management, customer feedback, management of external relations and environmental concerns;

- The entire system operationalized in a quality management system to ensure continual improvement.

Figure 4. Quality Assured Technical Education System

The public TVET providers include TESDA Technology Institutes composed of 59 schools, 15 Regional Training Centers, 43 Provincial Training Centers and 6 Specialized Training Centers. Other public TVET providers include State Universities and Colleges (SUCs) and Local Universities and Colleges (LUCs) offering non-degree programs; Department of Education supervised schools, Local Government Units (LGUs) and other government agencies providing skills training programs.

To ensure greater access, TESDA, through its Centers and designated providers, continues to undertake direct training provisions with four training modalities: school-based, center-based, enterprise-based and community-based. Enterprise-based training is carried out through the Dual Training System/apprenticeship while community-based training is done in collaboration with Local Government Units.

TESDA is the agency mandated by law (Republic Act No. 7796) to 1) promote and strengthen the quality of technical education and skills development programs in order to attain international competitiveness; 2) focus technical education and skills development on meeting the changing demands for quality middle-level manpower; 3) encourage critical and creative thinking by disseminating the scientific and technical knowledge base of middle-level manpower development programs; 4) recognize and encourage the complementary roles of public and private institutions in technical and skills development and training systems; and 5) inculcate desirable values through the development of moral character with emphasis on work ethic, self-discipline, self- reliance and nationalism.

Organizationally, the governance of TESDA, specifically its policy formulation and program approval, rests on a Board composed of representatives of government, industry and employers, workers’ unions and organizations and TVET providers. The composition of Board membership assures that it will be private sector led or dominated although the Board is chaired by the Secretary of Labor and Employment and the Co-chaired by the Secretaries of Education (basic) and Trade and Industry. The Board approves all the policies and plans of TESDA which are implemented by the TESDA executive and regional directors.

Higher Education

Graduate Education

Graduate education in the Philippines is expected to achieve a clear progression beyond baccalaureate/undergraduate education by underscoring integrative and interrogative teaching and learning contents and methods and recognizably higher competencies in knowledge production (research), knowledge transmission (teaching) and knowledge application (professional practice, vocational arts, technology).

Master’s and doctoral programs in the Philippines have two tracks: Academic or Research Track (PhD by Research) and a Professional Track. Since the Philippine higher education system is heavily influenced by the United States, Master’s or PhD degrees by research is a relatively recent development. The prevailing graduate curriculum is based on coursework with thesis/dissertation.

Lifelong Learning

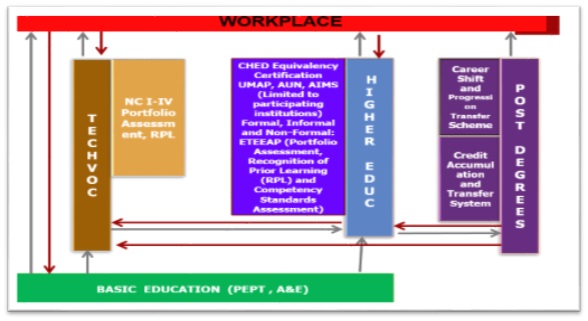

Lifelong learning entails the institution of pathways and equivalencies that enable individuals to weave in and out of the formal education system while acquiring competencies from non-formal and informal settings that could be credited towards formal qualifications in the formal system.

Such pathways and equivalencies are increasingly put in place to provide different routes to basic education for adult and overage learners. Their path will be determined by their life and employment experiences and their purpose for seeking basic education. The conceptual paradigm in Figure 6 shows the pathways and equivalencies between the formal and alternative basic education curricula and programs.

Beyond basic education, the Philippine Credit Transfer System (PCTS), currently still work in progress, would allow a seamless progression/transition between levels of qualifications. Figure 7 illustrates the possible movement between education levels facilitated through various access ramps or pathways of the respective professions/discipline covering mechanisms for both conventional and non-conventional learning.

FIGURE 6. Pathways and Equivalencies in Basic Education

[FLO=Flexible Learning Outcomes]

[FLO=Flexible Learning Outcomes]

Figure 7. Existing Pathways and Equivalencies Access Ramp

After completion of Senior High School, learners have the option to proceed to higher education, undertake technical vocational training or join the workforce.

Those interested in taking technical-vocational courses after high school may enroll in the various TESDA accredited programs and obtain National Certifications (NC) upon successfully passing the certification process or national competency assessment. National Certification holders may join the workforce at any time or may opt to pursue higher education with possible credits given to their NC or their qualification/competency upon assessment and evaluation or through ladderized education programs (LEP). These programs allow for a steady progression from certificate to diploma to degree learning.

Recognition of prior learning is conferred through validation of competencies achieved in nonformal or informal modes of learning in the Philippine Competency Assessment and Certification System (PTCACS). The validation system utilizes the same competency standards required in the Training Regulation and the system utilizes varied assessment methods applicable to those who achieved competencies through nonformal and informal means.

Programs providing credit transfer overlap, with some common learning, for which credit can be awarded. There can be credit obtained horizontally from one certificate program to another in a related field, opening career change opportunities for students. Academic degree holders may wish to strengthen their professional skills through addition of an applied technical-level diploma, with appropriate credit transfer from the degree into the diploma. Equivalency also covers associate qualifications which, by definition, bear full credit within a Baccalaureate degree.

Those pursuing college education on the other hand, may choose to accumulate learning credits through the Conventional mode such as formal schooling or through non-conventional modes such as transnational education or open and distance learning. Individuals may also obtain their college diploma through the recognition of prior learning and/or competency standards assessment. College learners may at some point exit school and be subjected to evaluation and assessment to determine their re-entry level. Those who obtain undergraduate diplomas may opt to pursue higher learning through graduate studies or join the world of work and return anytime to proceed to graduate school—while obtaining credits for graduate school-related competencies acquired informally or non-formally in the world of work.

It is worth noting that for the regulated professions, the Professional Regulation Commission and the Professional Regulatory Boards, in consultation with the Accredited Professional Organization/ Accredited Integrated Professional Organization, the Civil Service Commission, other concerned government agencies and stakeholders, are in the process of formulating and implementing Career Progression and Specialization Programs for every profession which shall form part of the Continuing Professional Development. Through Pathways and Equivalencies, the amount of learning earned from CPDs may be accumulated and transferred, allowing a professional to progress from one qualification to another, thus facilitating professional mobility and mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

To date, the PRC Regulatory Boards have already started drafting their respective Career Progression and Specialization. However, they still need to categorize the qualification title of each specialized area appropriate to specific level descriptors in the PQF. A series of workshops and dialogue with stakeholders is scheduled in 2018.

For other regulated qualifications such as in the aviation and maritime industry, the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP) and the Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA) are mandated by law to develop competencies and qualifications standards in accordance with the international conventions in International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) on Standards of Training, Certification & Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW), respectively.

Specifically, the CAAP issued the Philippine Civil Aviation Regulations (PCAR) Part II, based on pertinent ICAO requirements, which covers the regulated qualifications for pilots and mechanics adopted by the CAAP through a Board Resolution No. 2011-025 dated April 11, 2011.

The STCW Office of the Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA) provided the framewwork on the development of the Qualification designed and structured based on the International Maritime Organization (IMO) course format and is required under the 1978 Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) which sets the minimum qualification standards for masters, officers and watch personnel on sea going merchant ships. The Convention was significantly amended in 1995 and in 2010 the IMO Convention on STCW adopted a new set of amendements in Manila called “The Manila Amendments” to keep the training standards in line with the new technological and operational requirements that require new shipboard competencies.

The Philippine Qualifications Framework and the Philippine Education and Training System

- to adopt national standards and levels of learning outcomes of education;

- to support the development and maintenance of pathways and equivalencies that enable access to qualifications and to assist individuals to move easily and readily between the different education and training sectors and between these sectors and the labor market; and

- to align domestic qualification standards with the international qualifications framework thereby enhancing recognition of the value and comparability of Philippine qualifications and supporting the mobility of Filipino students and workers.

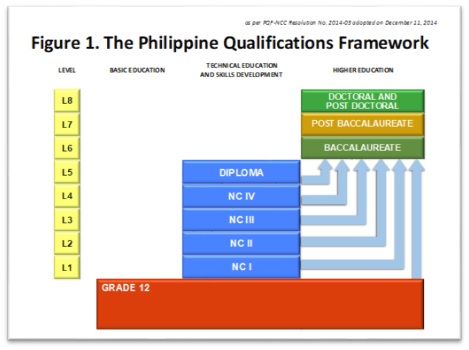

Mapping of Qualifications Against the PQF Levels

A mapping of the qualifications in the tertiary level educational subsectors against the PQF levels is shown below:

| Educational Subsector | Qualifications | PQF Level | PQF Level Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary | |||

| Technical Vocational Education and Training | National Certificate (NC) I | I |

|

| National Certificate (NC) II | II |

|

|

| National Certificate (NC) III | III |

|

|

| National Certificate (NC) IV | IV |

|

|

| National Certificate (NC) V | V |

|

|

| Higher Education | Associate Degree | V |

|

| Baccalaureate Degree | VI |

|

|

| Post-baccalaureate Degree | VII |

|

|

| Doctoral and Post-doctoral Degree | VIII |

|

The qualifications covered by the PQF are listed in the Philippine Qualifications Register.